We must stop normalizing hazing

- 4 mins

Recent Huffington Post article glorifies hazing as a bonding experience. The reality is much darker

The headline is provocative: “During A Night Of Hazing, I Confessed A Dark Secret To My Pledge Brothers. It Changed Everything.”

The commentary, published recently in the Huffington Post, is written by Tanner Aiello, who describes himself as the first openly gay member of his fraternity at the University of Southern California in 2018.

Aiello recalls his pledge process as three weeks of parties and alcohol-fueled conversations about his sexuality, culminating in “Beach Night.”

Late one night, Aiello and other pledges were ordered to walk two miles in the rain to a hidden beach where, Aiello wrote, “no one would hear me screaming.”

The young men spent the next six hours digging a deep pit in the sand, with fraternity members yelling at them to dig faster or issuing punishments like running sprints or swimming in the cold ocean.

The pledges were then ordered to climb into the pit and share their deepest secrets with their new “brothers.” They took turns telling stories of drug addiction, sexual abuse, eating disorders, and other traumatic experiences.

Aiello says his story ended well with fraternity members offering him support and a sense of belonging. “This brotherhood makes me realize what life’s all about — having a group of friends who love me. That’s all I can ask for,” he wrote.

The definition of hazing

Let’s be clear: What Aiello describes is hazing. And the suggestion that some hazing can be “good” is dangerous.

A widely used definition of hazing developed by our partners at StopHazing.org defines hazing as “any activity expected of someone joining or participating in a group that humiliates, degrades, abuses, or endangers them, regardless of a person’s willingness to participate.”

In this case, the fraternity used deception, forced exercise, sleep deprivation, exposure to the elements, fear, and potential humiliation to compel a sense of bonding among the pledges.

Elizabeth Allan, a leading expert on hazing at the University of Maine and principal of StopHazing, describes a continuum of hazing that scales up from intimidation and harassment to physical violence.

From "Animal House" to Caitlin Clark

Popular culture has long glorified hazing as a test of courage and a tangible demonstration of one’s desire to belong.

From the movie “Animal House” to the rookie hazing of WNBA star Caitlin Clark, hazing is often portrayed as team-building, good-natured teasing, or a time-honored tradition.

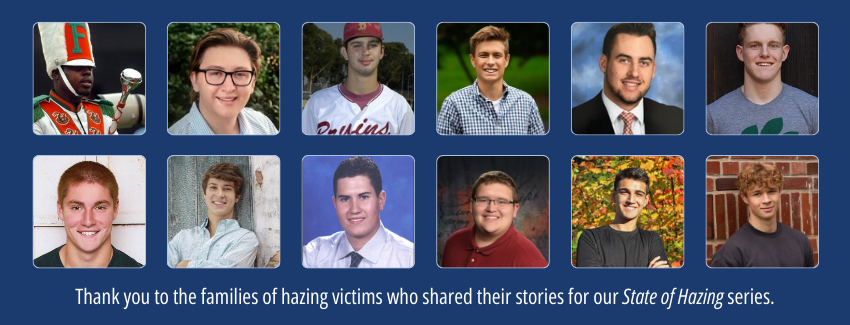

Yet we know that, nearly every year, at least one college student dies as a result of hazing on college campuses. Countless others are injured or traumatized by hazing.

Aiello’s experience could easily have ended in tragedy. What if alcohol or drugs had been involved, as they often are in hazing incidents?

What if someone in the circle that night felt coerced into telling a secret he was not ready to share?

What if fraternity members had used the shared secrets to harass, humiliate, or expose their pledges publicly?

We must stop normalizing hazing as a rite of passage and instead develop and share healthier team-building practices like these ones developed by StopHazing.

The real story of hazing at USC fraternities

As it turns out, there is much more to this story of hazing at USC.

In 2018—the same fall that Aiello was experiencing “Beach Night”—his fraternity, Tau Kappa Epsilon (or TKE), was on social suspension because of previous hazing cases. That same fall, four other USC fraternities were also suspended following separate hazing allegations.

In 2022, reports of sexual assaults at another USC fraternity, Sigma Nu, led the school to put in place new policies for school-sanctioned activities, including requiring security guards at parties and mandatory ID scanners, as well as a ban on kegs and large containers of alcohol.

Eight USC fraternities—including TKE—chose to disaffiliate and sever ties with the school rather than follow the new policies.

.jpg)