The state of hazing in America

A HazingInfo.org investigation finds hundreds of hazing incidents at universities across the US — while 50% of campuses fail to report hazing even when required by law

Learn about hazing on your campus: HazingInfo's Campus Lookup

Read more in our series: The state of hazing in Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, Texas, and Washington.

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of “The State of Hazing,” our blog series investigating the impact of state hazing laws that require public disclosure of hazing incidents.

Colleges and universities across the United States reported 946 incidents of hazing between 2018 and February 2025, according to a new analysis by HazingInfo.org.

It’s the first time the total number of reported US hazing incidents has been tallied, from minor incidents to serious injuries and deaths.

National hazing experts call that number disturbing, powerful — and likely just a small fraction of the true number of hazing incidents.

HazingInfo.org looked at colleges and universities in nine states that have hazing transparency laws. These laws require campuses to make available to the public a report on hazing incidents after the institution makes an official finding that hazing occurred in a student organization or team.

We found:

- 946 hazing incidents reported by 171 colleges and universities in nine states since 2018.

- Just 50% of schools in those states are publicly reporting their hazing incidents as required by their own state laws.

Hazing incidents in 9 states, 2018 to February 2025

.png?width=1024&height=768&name=State%20of%20hazing%20in%20America%20(1).png)

Source: HazingInfo.org. Data reflects incidents reported, investigated, formally determined to be hazing, and publicly reported by universities or media sources.

Why 946 hazing incidents still isn’t the full picture

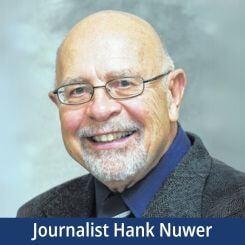

“Those numbers are the facts that we need to help end hazing,” said Hank Nuwer, an author and journalist who has spent the past 50 years investigating and documenting hazing deaths nationwide.

“Every time we have a death from hazing, people pay attention,” Nuwer said. “But we also need to understand how widespread hazing is on campuses.”

Nuwer estimated there were 40 to 60 incidents of hazing for every reported death from hazing on the campuses he investigated while researching his 2001 book, “Wrongs of Passage: Fraternities, Sororities, Hazing, and Binge Drinking.”

Dr. Elizabeth Allan, a top US hazing researcher, called the number “so disturbing, but not surprising … When you don’t have access to data like this, it’s easy to think it’s not happening. Even when you know better,” she said.

She believes the 946 incidents HazingInfo found “are just the tip of the iceberg.” Her research has found that 95% of students who experience hazing do not report it.

Allan, who leads the Hazing Prevention Research Lab at the University of Maine, noted that the number only reflects hazing incidents in nine states and only from the 50% of institutions that are meeting their legal obligations to report hazing.

Even when cases are reported, many are labeled by colleges and universities as alcohol violations, disorderly conduct, assaults, or other types of violations — but not as hazing, said Allan, principal at StopHazing.org.

Hazing by the numbers

In total, HazingInfo searched for hazing incident reports at 466 higher education institutions in the nine states: Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.

We collected data from the 233 institutions we found that make their reports public.

We also included credible media reports about hazing cases when they were not already included in the institution’s report.

HazingInfo did not include alcohol violations, assaults, or other types of organizational misconduct that were not formally determined by the school to be hazing-related.

“People have the right to that information”

Rae Ann Gruver successfully pushed for hazing transparency laws in Georgia and Louisiana following the 2017 death of her son, Max, from hazing at Louisiana State University (LSU).

She called the numbers disappointing, particularly the number of campuses meeting their state’s hazing transparency requirements. Louisiana ranks last among the nine states, with just 4 out of 22 higher education institutions providing public access to a hazing transparency report.

Gruver has already started contacting local universities to seek answers about why they aren’t reporting hazing as required.

“Universities need to understand this is not about tarnishing your name. It’s about the safety of your students,” Gruver said. “People have the right to that information. If you have that information, you need to be transparent about it.”

Many hazing reports dismissed by universities

HazingInfo’s investigation found other notable trends in the hazing incident data we gathered:

- The overwhelming majority of hazing incidents in the nine states involved fraternities, sororities, and athletic teams.

- Many hazing reports end up dismissed by colleges and universities that say they can’t substantiate the allegations. For example, the hazing report posted by Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania shows five instances of hazing between 2019 and 2024 that were formally ruled to be hazing. Seventeen additional hazing allegations were deemed unfounded following university investigations.

- Many schools start reporting hazing incidents in the years following the passage of state hazing transparency laws. But the updates may stop after a few years. For example, Seattle University does not appear to have updated its incident report since 2022, when Washington enacted its hazing transparency requirement, known as Sam’s Law.

- Some campuses make it difficult to find hazing incident data on their websites. Louisiana State University has a hazing prevention website that doesn’t show its list of hazing violations. Instead, their report is buried under the title “Community Scorecard” and requires multiple clicks through all 40 of its Greek organizations to determine that 18 organizations have violated the school’s hazing policy since 2018. It only includes information on Greek organizations, not athletic teams or other student clubs.

- It’s not always clear when an incident is hazing-related even when the university finds a violation. At LSU, officials sometimes use the term “coercive behavior” to describe serious violations that appear to be hazing-related.

- Some campuses do not name the organizations charged with hazing, limiting how useful that information is to parents and students. At Drexel University in Pennsylvania, nine instances of hazing between 2018 and 2023 are attributed to unnamed fraternities and sororities and one athletic team.

Hazing’s ripple effect of harm

Each of the 946 hazing incidents identified in HazingInfo’s investigation likely represents multiple victims and offenders, experts say.

“It could be 30, 40 people at a time involved in these incidents,” Nuwer said.

Hazing often happens over a period of time, so a single report of hazing could represent weeks of hazing abuses, he added.

Beyond the harm hazing causes to victims, the ripple effect on friends, families, classmates, and campuses is also worrisome, Allan noted.

“It’s part of the reason we work to make the case that the issue of hazing is not just about individual bad groups. It’s a campus-wide issue,” she said. When hazing isn’t acknowledged or punished, “that sends a message and sets a tone for the campus climate and risks normalizing the behavior.”

What keeps hazing reports from becoming public

It isn’t easy for a hazing allegation to find its way into a report that anyone can see online.

“It’s a long distance between hazing happening … and finding an organization responsible for hazing,” said Doug Fierberg, a lawyer who specializes in representing hazing and school violence victims.

The vast majority of students who experience hazing don’t report it. In many cases, they don’t even recognize their experience as hazing, he said.

“Or sometimes frat kids circle the wagons and lie because they swear an oath of loyalty to their brotherhood,” Fierberg said. “They take that literally and don’t want to ‘out’ the fraternity and face retaliation or be driven off campus.”

Some who do report hazing do so anonymously out of fear of potential backlash, Allan said. They may not provide much information, making it difficult for campus staff to investigate.

“We hear that a lot from campus professionals who want to get to the bottom of things for the sake of campus safety but often feel thwarted” when there aren’t enough details to determine what happened or who was involved, she said.

Universities face training, capacity issues

In other cases, campus staff may look the other way because of the time and resources it takes to conduct a thorough investigation, Allan said. That’s especially true if the incident hasn’t made headlines or resulted in a serious injury or death.

Smaller campuses may not have the bandwidth or training to undertake an investigation, Nuwer noted.

The turnover rate among student affairs professionals can be high, he said, and their offices are frequently understaffed, leading to burnout and a lack of training to recognize and pursue hazing allegations.

The lack of a consistent and clear definition of hazing can also lead to confusion for campus professionals, he said.

The dean of students or other campus leaders “may be perfectly happy to have it all go away,” Nuwer said. “Or the victim decides to drop it. That happens all the time.”

Student organizations find ways to duck responsibility for hazing

Student organizations under investigation will sometimes align their stories in advance, making it hard for investigators to discern the truth, Allan said.

“You just hear the same words over and over, and you know they have already communicated with each other about what their story is going to be,” she said. “It’s very hard to break through that.”

The organization may bring in lawyers to represent individuals or the national headquarters, which can slow things down, Allan said.

Sometimes, when a formal finding of hazing is imminent, a fraternity will voluntarily withdraw from the university for a couple years, Fierberg said.

Hazing may be labeled as a “violation of internal risk management rules” or use other words to mask the truth before the organization returns to campus.

How campus influencers can shut down a hazing investigation

And then there are the campus politics involved in making a hazing report public.

“There is a fear of reputational damage that administrators have. They don’t want to be associated with this kind of bad press,” said Tim Marchell, who championed hazing transparency at Cornell University as director of health initiatives until his recent retirement.

Fraternities, sororities, athletic departments, alumni, team boosters, and other groups have influence on campus, he said, and may exert it to keep hazing hushed up. At some schools, university administrators and members of the boards of trustees may have been involved in groups that hazed during their undergraduate years.

“A lot of this has to do with universities not wanting to air their dirty laundry,” he said.

Maybe the decision is made to handle a hazing case internally so the team doesn’t have to forfeit a game or the fraternity doesn’t get suspended, Marchell said.

Universities may also discourage investigations that could affect their alumni and financial donors, Allan said.

“Alumni do often get involved, and they are going to have the ear of the president or chancellor,” she said.

And sometimes, even with a careful investigation led by the university, there may be external politics at play. Nuwer said he reported on a hazing case in which the entire investigative file was “disappeared” by the local prosecutor.

New federal law requires all universities to report hazing

A new federal law requiring colleges and universities to publicly disclose hazing incidents may be a game-changer for understanding the full scope of hazing, experts say.

By December, most of the nation’s 2,600-plus, four-year colleges and universities must publish a Campus Hazing Transparency Report on their public websites that summarizes findings against any student organization for hazing violations.

The new Stop Campus Hazing Act, signed by President Biden in December, will also require a second hazing transparency report that includes all hazing incidents reported to campus security or local police — not just those that ended in a formal finding of hazing.

That data, to be submitted to the US Department of Education, will likely provide a more complete picture of campus hazing once the information is available in 2026.

Transparency about hazing could help end it

The new law is part of the reason that Marchell said he has never felt more hopeful about the progress of hazing prevention efforts, “although I’m under no illusions about the complexities of hazing…and how entrenched it is.”

While the scientific research on hazing prevention is still limited, Marchell co-authored a 2022 study with Allan that found a measurable decrease in reported hazing by students following Cornell’s implementation of a new, public health-focused hazing prevention program that included a transparency requirement for hazing incidents.

“For our society to deal with this problem effectively, we have to be honest about what’s going on,” Marchell said. “Parents and students need to be informed, and organizations and institutions need to have accountability.”

The end of pledging?

Fierberg and Nuwer both say there is another way to end hazing: Get rid of the pledging process.

“Until pledging ends, these numbers (of hazing reports) are going to be high, despite the laws,” Nuwer said.

A weeks-long pledging process, in which potential new members are expected to show they are “worthy” to join the organization, may be framed by the group as tradition, but that is often just another word for hazing, Fierberg said.

For too long, fraternities—especially their national organizations—have gotten a pass for the hazing that happens in their chapters, Fierberg said.

“It’s simple: If you are the organization that is hurting and killing people, why isn’t the focus on making you address that?” he asked. “It’s like they have farmed out the oversight and management to the universities.”

Why aren’t fraternities footing the bill for the university staff who are required to investigate, adjudicate, and report on hazing by their member chapters? Fierberg asked.

Ultimately, it’s the fraternity members themselves, many still in their late teens and early 20s, who are being asked by fraternities and universities to police themselves.

“That’s who is making the life-and-death decisions on a given Saturday night about whether the pledging process is going to involve handles of alcohol, whether police are going to be called, whether anyone is going to watch over the pledges after a night of drinking,” Fierberg said.

“Somehow, it’s all left in the hands of 18-, 19-, 20-year-olds,” he said.

Next in "The State of Hazing" blog series: A state-by-state look at hazing data in each of the nine states.