77 hazing incidents since 2018: The state of hazing in South Carolina

The state’s Tucker Hipps Transparency Act requires most public universities to disclose hazing incidents, but private schools and The Citadel are exempt

Editor’s note: This is part of our blog series, “The State of Hazing,” investigating the impact of hazing laws in nine states that require public disclosure of hazing incidents.

Thirteen South Carolina colleges and universities reported 77 campus hazing incidents between 2018 and early 2025, according to a new HazingInfo.org investigation.

But two-thirds of the state’s higher education institutions—including all private schools and The Citadel, the state’s military college—are exempt from the state’s hazing transparency law.

The state’s Tucker Hipps Transparency Act also only applies to hazing incidents that happen in fraternities and sororities, excluding athletic teams, marching bands, and other student organizations where hazing has been documented.

That makes it nearly impossible to get a full picture of the extent of college hazing in South Carolina.

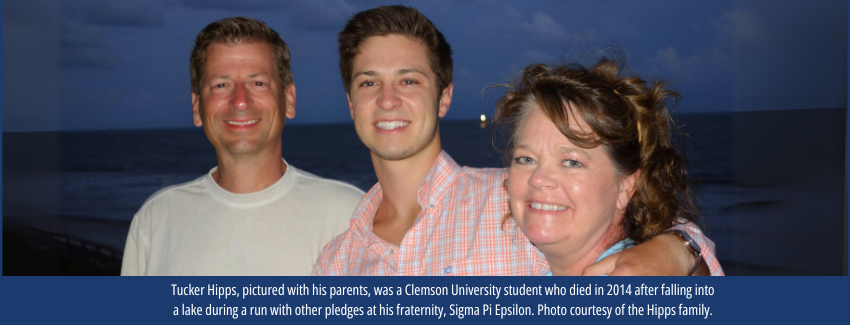

“More accountability is needed,” said Cindy Hipps, whose son, Tucker, died from hazing at Clemson University.

“I think more people are aware of hazing with the transparency law, but it depends on who is in charge at each university,” said Hipps, who has worked with several universities in South Carolina to improve hazing reporting and prevention programs.

“You have to stay focused on it 24/7. You can’t let up.”

All South Carolina public universities in compliance with state law

South Carolina is one of nine US states with laws or policies requiring campuses to post hazing incidents online. It is the only one of the nine states that exempts private institutions from reporting hazing.

South Carolina college hazing data, 2018 to February 2025

.png?width=1545&height=2000&name=South%20Carolina%20(2).png)

Across the nine states, the HazingInfo.org investigation found 946 reported hazing incidents on 171 campuses between 2018 and February 2025. It is the first time the total number of reported US hazing incidents has been tallied.

Each public institution in South Carolina is currently in compliance with state law. Some schools choose to include more information than the law requires.

The HazingInfo investigation only included misconduct that each institution formally determined to be hazing. It omitted other kinds of misconduct like alcohol violations or assaults that weren’t officially labeled as hazing.

The Post and Courier newspaper in Charleston recently built its own database of hazing incidents in South Carolina colleges dating back to 2011. They found 124 reported hazing incidents during that time period and inconsistency in the level of detail provided by different universities when they report organizational misconduct.

Twenty-five of South Carolina’s 33 higher education institutions have a hazing policy, while just 16 campuses provide an online reporting form for students and others to report hazing.

"I still don't see the culture changing"

Cindy Hipps believes hazing goes through cycles and “seems to be coming back up now,” she said. “I know of three incidents at Clemson that haven’t even been reported yet.”

of three incidents at Clemson that haven’t even been reported yet.”

Just in the past year, 15 hazing incidents have been reported at six different South Carolina campuses, according to HazingInfo’s data.

It’s been 11 years since Tucker Hipps went on an early-morning run at Clemson with members of Sigma Phi Epsilon and didn’t return. His body was found later that day in a local lake. Witnesses reported that he was forced to walk a bridge railing as punishment because he didn’t bring breakfast biscuits for other students on the run.

No one was ever charged.

“I still don’t see the culture changing,” said Hipps, who created the Tucker W. Hipps Memorial Foundation in her son’s memory. “The kids, they’re the ones that have to change the culture of tolerance. They know what they can and will not put up with.”

But Hipps also believes fraternity alumni play a role in perpetuating hazing within the chapters they advise. “It’s always been my belief that the national (organizations) could change the culture,” she said.

After Tucker’s death, Hipps channeled her grief into hazing prevention advocacy to pass the law named after her son and to raise awareness about hazing.

She worked with Clemson’s Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life to develop an eight-week health and wellness program providing training and support for fraternity and sorority pledges and members serving as their mentors, with hazing prevention at its core.

“It encouraged relationship-building … and peer accountability,” said Joe Strickland-Burdette, who served as Clemson’s associate director of fraternity and sorority life. He is currently director of residence life at Piedmont University in Georgia.

“You have more success when students are holding other students accountable,” he said.

Many hazing reports are never publicly disclosed

South Carolina law requires the state’s Commission on Higher Education to publish an online report with links to each school’s hazing incident report.

Karen Woodfaulk, director of the commission’s Office of Student Affairs, said she and her team check each link to make sure institutions are complying with the law and follow up when schools are late in providing their reports.

That’s different from many other states, where hazing transparency laws don’t include an enforcement or oversight role.

Like many states, South Carolina’s hazing transparency law requires reporting of “actual findings” of hazing and other code of conduct violations. That means many hazing incidents don’t make it into public reports because they are resolved or dismissed before a formal finding of hazing is made.

Woodfaulk believes the data is still valuable for parents and students as they make decisions about joining campus groups.

But it’s important to know that “what you’re seeing is the outcome of a process … it’s not who was charged, but who ended up with the infraction,” she said.

Families should consider the reports a starting point and keep digging for additional information to get a more complete picture, Woodfaulk said.

More safeguards for students reporting hazing

When hazing is reported, it often comes in anonymously and without enough information for campus officials to follow up.

“I can’t tell you how frustrating that was for me as an adviser. There’s nowhere you can go with that,” Strickland-Burdette said.

He thinks amnesty or “Good Samaritan” laws that offer legal immunity for students who witness hazing and report it could help encourage more detailed hazing reports.

Yet students remain fearful of their names becoming public if they report hazing, he said. He’s known students who have transferred or dropped out of school after making a report because they were treated “like pariahs” after calling out hazing in their teams or groups.

A cross-campus collaboration to prevent hazing

Furman University in Greenville voluntarily reports its hazing incidents online, the only private institution in South Carolina to make that information public. The school reported seven hazing incidents in the past five years.

South Carolina to make that information public. The school reported seven hazing incidents in the past five years.

That reflects the university’s overall goal of transparency and cross-campus collaboration to address hazing, said Rod Kelley, assistant dean of student conduct.

Furman is intentional about bringing together higher education professionals from many departments and disciplines to prevent hazing, he said, including people from fraternity and sorority life, athletics, the music department, and campus police.

Rituals and traditions “can get twisted very quickly and lead to power imbalances” within a student group that can lead to hazing, he said. “It’s about changing the culture.”

That focus on hazing transparency puts Furman in a good position to implement the requirements of the Stop Campus Hazing Act, a new federal law that will require all US colleges and universities to publicly disclose hazing incidents on their websites by December 23.

First statewide hazing prevention summit brings campus pros together

Culture change and student education is also a big part of hazing prevention at the University of South Carolina-Columbia (USC). The state’s largest university, USC also has the greatest number of reported hazing incidents, with 27 cases reported since 2018.

“The more you talk about it, the more you can encourage the reporting, the more you’re going to hear about it,” said Carli Mercer, USC’s director of fraternity and sorority life. “When you amp up the reporting resources, you’ll see an uptick in the number of reports coming in.”

about it,” said Carli Mercer, USC’s director of fraternity and sorority life. “When you amp up the reporting resources, you’ll see an uptick in the number of reports coming in.”

USC has shared its hazing incidents publicly since before the Tucker Hipps Act went into effect, Mercer said, and the university includes all student groups in its hazing reports, not just fraternities and sororities.

“We want to learn about hazing before it snowballs, to keep everyone safe and knock it down in an organization before it gets out of hand,” she said.

This week, USC is hosting campus professionals from 14 South Carolina colleges and universities at the state’s first hazing prevention summit to learn from experts at the research organization StopHazing about prevention strategies and incident reporting laws.

“How can we change that culture over time and reduce the harm, reduce the risk?” asked Mercer, one of the summit organizers. “How can we help provide a positive team-building experience and show them how to build a brotherhood or sisterhood without singling out or harming someone?”

Mercer believes this generation of students has a lower tolerance for hazing.

“We’ve seen more direct reporting than we did before, coming directly from the potential new members,” she said. “That definitely gives us hope.”

____________________

Learn about hazing on your campus: HazingInfo's Campus Lookup

Read more in our series about the State of Hazing in Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.