999 hazing cases later, here’s what I learned about college hazing in America

HazingInfo’s deep dive into hazing in nine states reveals many colleges ignoring a pervasive problem — and some possible solutions

Learn about hazing on your campus: HazingInfo's Campus Lookup

Read our State of Hazing series: Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.

%20(5).png?width=1600&height=250&name=SOH%20Banner%20and%20text%20bugs%20-%20HI%20Blog%202025%20(1600%20x%20250%20px)%20(5).png)

Editor’s note: This is the final installment of “The State of Hazing,” our blog series investigating the impact of state hazing laws that require public disclosure of hazing incidents.

Is hazing really still a problem on today’s college campuses? I spent nine months studying reported hazing cases at nearly 460 US colleges and universities.

I found stories of students being waterboarded, lit on fire, beaten, poisoned, and committing suicide following intense physical and psychological hazing.

These are just the cases we know about because one person reported it and another took the time to investigate.

The conclusion is clear: Hazing remains a very real threat to college students — and too many colleges and universities are failing in their responsibility to protect students from harm.

HazingInfo found 999 reported hazing incidents in nine states between 2018 and 2025.

We chose these nine states because their laws require public disclosure of hazing incidents on college websites — yet we found only half of campuses in those states are complying with their state law.

Here are three more takeaways from our series on the State of Hazing in America and potential solutions to help make campuses safer.

Most hazing incidents we know about would still be secret without the families of hazing victims demanding transparency and accountability.

Families who have lost children to hazing are the driving force behind laws in the nine states that have passed hazing transparency legislation.

In each state, families worked with key state lawmakers to pass new laws requiring colleges and universities to publish hazing incidents on their websites. Families shared their deeply personal stories of loss over and over again to convince sometimes-reluctant legislators to bring hazing into the light.

Still, some families are disappointed and frustrated that their efforts haven’t led to a decrease in hazing. Some are simply tired of the fight.

“You have to stay focused on it 24/7. You can’t let up,” said Cindy Hipps, mother of Tucker Hipps, who died from hazing in 2014 at Clemson University in South Carolina. “I still don’t see the culture changing.”

“You have to stay focused on it 24/7. You can’t let up,” said Cindy Hipps, mother of Tucker Hipps, who died from hazing in 2014 at Clemson University in South Carolina. “I still don’t see the culture changing.”

“I’m trying to be optimistic that we’re making a difference … but how do you measure that?” said Evelyn Piazza, who lost her son, Tim, to hazing at Pennsylvania State University in 2017.

The lack of penalties and oversight in state law means many campuses ignore hazing transparency requirements.

Here’s what happens after a state law is passed: Some colleges and universities start off right by releasing their hazing incident data. They publish new web pages with information on their hazing incidents and approach to hazing prevention.

And then, after a year or two, they just stop reporting. It’s a pattern repeated in every state that has passed a hazing transparency law.

Across the nine states, just 50% of colleges and universities are publishing their hazing incidents as required, according to HazingInfo's State of Hazing series.

In Virginia, for example, many campuses still aren’t clear about who is responsible for implementing Adam’s Law, a 3-year-old state law that requires colleges to post hazing incidents online.

.png?width=187&height=187&name=VA%20SOH%20Inset%20Image%20Small%20(1).png) “It feels like an honor system,” said Rachael Tully, assistant dean of students at Virginia Commonwealth University, where Adam Oakes died from hazing in 2021. “I think how people view the requirements is: What’s the consequence? Who is even confirming (the report) is up? Three years in, who’s following up?”

“It feels like an honor system,” said Rachael Tully, assistant dean of students at Virginia Commonwealth University, where Adam Oakes died from hazing in 2021. “I think how people view the requirements is: What’s the consequence? Who is even confirming (the report) is up? Three years in, who’s following up?”

“You have to have consequences,” said Julie DeVercelly, who lost her son, Gary Jr., in 2007 to hazing at Rider University in New Jersey. “You have to have people who are trained, … a site that collects all the data, a review and audit process.”

We need new solutions to end hazing — because what we are doing now is not working.

There is no single solution to stop hazing. The problem is complex, pervasive, cultural, and multigenerational.

It will take a similarly nuanced set of actions — and committed, consistent effort — to end it.

The good news: There is no shortage of ideas from campus professionals, advocates, and victim families on hazing prevention strategies that can make a difference.

Four promising approaches to end hazing

Start hazing education in high schools — and don’t forget the parents. While there’s a lot of discussion of bullying in high school, it’s rare for high school students to learn about hazing before college.

Hazing is distinct from bullying, which is meant to exclude a person from a group. Hazing is any activity expected of someone joining a group that humiliates or endangers them.

Some hazing victim families are starting to focus their efforts on high school students and parents. The Oakes family helped pass a bill that requires hazing awareness and prevention training in Virginia’s high schools. They also created a hazing prevention curriculum that they gave to high schools.

The family of Stone Foltz, killed by hazing at Bowling Green State University in Ohio in 2021, has also focused on providing hazing prevention education to high school students and parents.

“If Stone had any type of education on hazing, he would still be here,” said his mother, Shari Foltz. Her family is working with lawmakers to get hazing education included in every Ohio high school’s required 9th grade health class.

National fraternities must be part of the solution. Right now, they are part of the problem. The same fraternity names come up again and again across the country when hazing incidents come to light. They include Alpha Tau Omega, Delta Kappa Epsilon, Phi Gamma Delta, and Sigma Chi.“It’s always been my belief that the national (organizations) could change the culture,” Hipps said.

Fraternity alumni often play a role in perpetuating hazing in their old chapters. In 2025, five former Omega Psi Phi members were charged with beating Southern University student Caleb Wilson to death during a hazing ritual.

Universities sometimes discourage investigations that could affect their alumni, who are among their biggest financial donors.

“Alumni do often get involved, and they are going to have the ear of the president or chancellor,” said Elizabeth Allan, a top hazing researcher who leads the Hazing Prevention Research Lab at the University Maine.

Shouldn’t national fraternities foot the bill for university staff who are required to investigate, adjudicate, and report on hazing that happens in their chapters? asked Doug Fierberg, a lawyer specializing in hazing and school violence cases.

Shouldn’t national fraternities foot the bill for university staff who are required to investigate, adjudicate, and report on hazing that happens in their chapters? asked Doug Fierberg, a lawyer specializing in hazing and school violence cases.

“It’s simple: If you are the organization that is hurting and killing people, why isn’t the focus on making you address that?” he asked. “It’s like they have farmed out the oversight and management to the universities.”

Fierberg’s recommendation: Eliminate the pledging process. If students are good enough to be accepted into the university, they should be good enough to join any campus club, team, or organization.

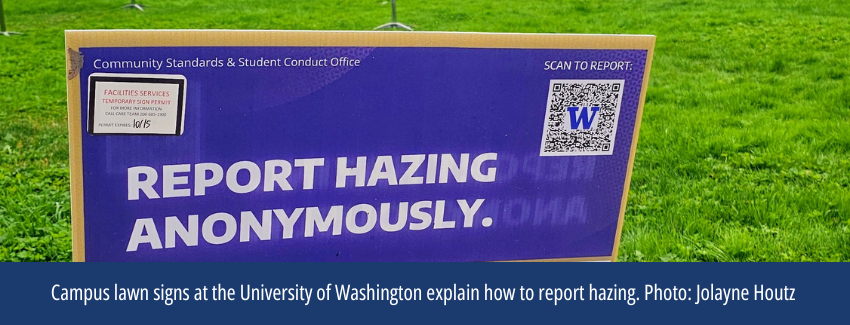

Teach students how to report hazing — and offer amnesty for those who come forward. Fear of retaliation means most students don’t report hazing. They don’t want to get their team or organization in trouble and risk facing blowback on campus.

Even when they do report, it’s often anonymously and with too little information to follow up.

Even when they do report, it’s often anonymously and with too little information to follow up.

“I can’t tell you how frustrating that was for me as an adviser. There’s nowhere you can go with that,” said Joe Strickland-Burdette, director of residence life at Piedmont University in Georgia. He formerly worked at Clemson University, where Tucker Hipps died.

Amnesty or “Good Samaritan” laws that offer legal immunity for students who witness hazing and report it can help encourage students to come forward.

Amnesty should also extend to student leaders who come clean about hazing in their organizations and seek help to change their organization’s culture, said Tully at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“A lot of them don’t know how to do it alone, and they’re afraid to talk to anyone about it,” she said.

Campus professionals in charge of hazing prevention need the full support of their colleagues — and bosses — across campus. A single online training course or a week of activities for National Hazing Awareness Week does not demonstrate real commitment to student safety.

Campus culture matters, starting at the top. Does the president or vice president of a university think hazing is an important issue? asked Francisco Lugo, director of Fraternity and Sorority Life at Georgia Southern University.

That sets a tone and helps get campus-wide buy-in and commitment to hazing prevention.

Hazing prevention should be comprehensive, with involvement from campus leaders in Fraternity and Sorority Life, Athletics, Student Conduct, Campus Health, Student Life, and beyond, many hazing prevention advocates say.

A new era starts now: National Campus Hazing Transparency Reports

In the coming weeks, we will get our first look at the most comprehensive national picture of hazing ever available.

Every college and university in America — public and private, small and large — must now publish a new Campus Hazing Transparency Report, required under a federal law passed in 2024. Families and advocates of hazing victims led the effort again to get the law passed.

Experts expect an uptick in reporting and awareness of campus hazing. Eventually, there will be financial penalties for campuses that fail to comply with the transparency law. HazingInfo’s research suggests many colleges and universities will not meet the requirements anyway, at least at first.

It will take time to know whether the national picture of hazing that emerges from the new data will be enough to compel campus leaders, national fraternities, and other student organizations to finally take the serious steps necessary to end hazing.

_______________________________

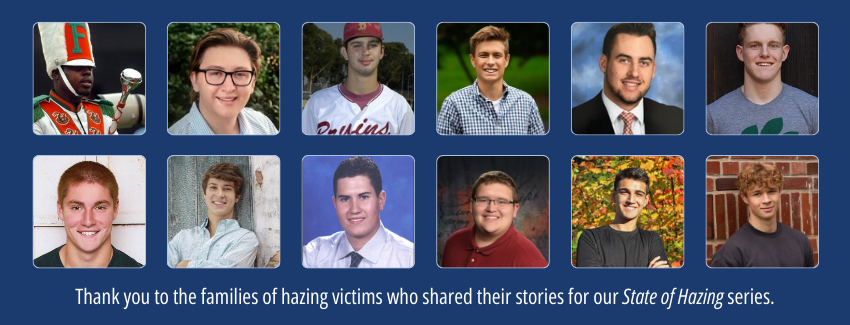

HazingInfo is profoundly grateful to the families of hazing victims who have worked tirelessly on hazing prevention and shared their stories with us for our State of Hazing series: The families of Robert Champion (died at Florida A&M University), Max Gruver (died at Louisiana State University), Gary DeVercelly Jr. (died at Rider University, NJ), Stone Foltz (died at Bowling Green State University, OH), Tyler Perino (injured at Miami University, OH), Collin Wiant (died at Ohio University), Timothy Piazza (died at Pennsylvania State University), Tucker Hipps (died at Clemson University, SC), Clay Warren (died at Texas Tech University), Adam Oakes (died at Virginia Commonwealth University), Sam Martinez (died at Washington State University), and Luke Tyler (died at Washington State University).

Read our State of Hazing series: Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.